The Race Class Narrative Research, Explained

Why these messages work, and who they turn out and persuade

"If you can convince the lowest white man he's better than the best colored man, he won't notice you're picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he'll empty his pockets for you." - Lyndon Johnson

“This is a guy who, although he’s much too liberal for Florida — I think he’s got huge problems with how he’s governed Tallahassee — you know, he is an articulate spokesman for those far-left views, and he’s a charismatic candidate. The last thing we need to do is to monkey this up by trying to embrace a socialist agenda with huge tax increases and bankrupting the state.” - GOP candidate for Florida Governor-R, regarding his opponent Andrew Gillum

As a candidate or staffer, you’re probably reluctant to wade into fraught, complicated racial territory, especially if you’ve been assured that sticking to economic arguments is your best bet. It’s possible you may not need to. There’s certainly no reason to depart from basic campaign best practices like focusing on the kinds of local issues that usually win local races.

But you also know you need to turn out your base and, for most progressive candidates, that means speaking truth to issues of racial justice. Further, you may find you have no choice in the matter: playing on white identity and racial fears has become a staple tactic for right-wing campaigns. Race has shaped so much about American life: choices we make about school funding, the balance between government and corporate power, and even whether we deem taxes wasteful supports for the “undeserving.” This campaign cycle may include questions about Black Lives Matter, kneeling during the National Anthem, police violence, sanctuary cities, high profile incidents of violence by an immigrant. It’s not enough to just refute these emotionally powerful arguments with facts. And even if your opponent or an independent group opposing you don’t raise these issues initially, they may do so as a late hit, with a mailer on the last weekend of the campaign, for example.

The good news is that we now have a powerful, positive story to tell to counter these attacks, engaging our base and persuading the middle. One way to contend gracefully with racially divisive attacks is to be ready with good answers - if your campaign has a briefing book, keep these articles in it. But the other way is to start working positive, inclusive messages about race into your campaign whenever possible. Even if it’s not the main focus of your positioning, including these messages as part of your overall appeal can help inoculate voters against divisive messages.

Why these messages work

They’re based on deep neuroscience - but like all effective messages, the reasons they work are quite straightforward:

They unite people. Research shows that people are feeling an acute sense of division in our country right now, so a story about purposeful division based on race lands in a way that might have seemed conspiratorial or inside baseball even a few years ago. They resonate with real people and their lived experiences right now, and when you start using them, you’ll witness this reaction immediately.

They draw clear distinctions. We’ve identified that persuadables are toggling between regressive and progressive racial narratives in their heads; the right is working to activate the former; we are either countering that with a progressive racial narrative or we're off the playing field, ceding the terrain.

They’re simple. The basic format of these messages has three parts. They start with a shared value, then name a specific villain engaged in deliberate division, and end by offering an aspirational path forward. Based on the examples we’re providing, you’ll be able to generate more of your own based on this simple formula.

Who these messages work for

These stories work because they tap into a deep, aspirational desire that large majorities of Americans hold to live in a thriving, multiracial society, and to work together to create that reality. While our research focused nationally, we also conducted more detailed surveys in four states: California, Indiana, Ohio and Minnesota. We found that while the most effective messages are always tuned to specific audiences, the common themes these messages share work as well in East Oakland as they do in East Ohio.

We considered the electorate in terms of three broad groups: our base, the opposition, and the largest group, persuadables. Keep in mind that these segments were generated by the data collected, as opposed to partisan identity or demographics and do not necessarily correspond to voting behavior. The base as defined here are the people who agree with progressive views regarding race, the role of government, and the economy.

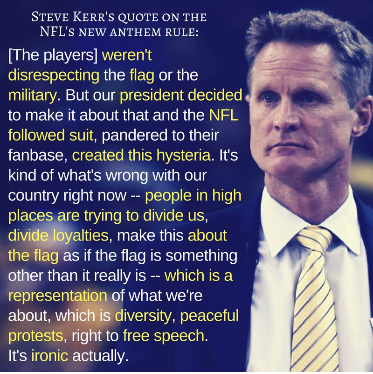

Our base (roughly 23% nationally) - These messages do more than reflect how our base views the world. They are also easily memorized, repeated and shared. (and yes, we tested how likely people would be to share them!) These messages have penetrated popular culture, making them easier for our campaigns to amplify. This is a good example, from the coach of the Golden State Warriors -

The opposition (18%) - These messages do not persuade opposition voters - by design. Instead, we seek to distance ourselves from these respondents drawing a clear line between what most voters believe and making the opposition’s position clearly the outlier. A message that appeals to everyone is a message that says nothing. It lacks the heat required to break through the constant political noise and fails to motivate our base into repetition and action.

Persuadables (roughly 59% nationally) - Persuadables tend to hold contradictory opinions, like agreeing that “focusing on race doesn’t fix anything and may even make things worse” while also agreeing that “focusing on race is necessary to move forward toward greater equality.” While trying to communicate with this group can be frustrating, it’s important to remember that for this significant majority of people, they just need to hear our story as much or more as conservatives’ story. These are normal people whose lives don’t include much time for deep engagement about political issues. But this research found conclusively that we can reach and persuade this group of voters.

Racial and economic injustice are challenging issues, but the core of this research is a powerful call to unity. A common right wing tactic has been to deploy racially-coded attacks, feign innocence, and then accuse us of “making it about race.” The call to unity is critical to how we defuse these attacks. Trump, Russians and the alt-right want to divide us, but this research has provided a framework that we can use to turn these craven attacks to our advantage by exposing them.